After years of living a nomadic existence, in early 2020 it became clear that having a proper home again would be a good idea. At the time, I was holed up in a 1930’s bungalow in Monterey, California writing the essays for my book Still Lives. Before I was set to leave, a neighboring bungalow came up for rent and I have called it and Monterey home ever since. Having been raised an hour north, I made visits to the Monterey Peninsula throughout my life, but most often it was Carmel-by-the-Sea or Big Sur that were my destination. It wasn’t until I was living in Monterey, that I began to investigate the history of this storied town more deeply.

As any good amateur historian knows, Monterey is known as “Steinbeck Country”– a compelling enough reason for me to dig in further to the characters and places that captured the author’s imagination. Most notable among them is Ed Ricketts, best friend to Steinbeck and a pioneer in the world of marine biology, known to many as “Doc” in Steinbeck’s novel Cannery Row. Ricketts legend is almost as towering as Steinbeck’s in Monterey. He founded Pacific Biological Laboratories, which went on to become a vital (and unlikely) cultural center for Monterey’s artists, writers, thinkers and musicians; it was even the birthplace of the Monterey Jazz Festival. PBL still sits at the heart of Cannery Row preserved in its last incarnation as a men’s club of sorts and open for tours one day a month. I, of course, was eager to visit and when I did, was inspired to make this set of images. It is a unique time capsule that straddles art, science and culture and preserves a time in Monterey long past.

The following is my essay called “Doc’s Lab” on PBL and it’s legacy. It was originally published in the Wildsam Field Guide of Big Sur & Hwy 1 in Fall 2022.

A factory steam whistle still blows at noon every day on Cannery Row, its sigh as much a nod to the street’s former life as the heart of Monterey’s sardine industry as it is theater for the aquarium visitors who largely people the street today. When I first heard that whistle, I was tucked in a sky-blue ı930s bungalow, not far away, on a writing deadline for my fourth book. My writing schedule tends to be monastic–eat, write, sleep, repeat–with the occasional fall down a research rabbit hole. But that steam whistle, marking my time as it would have if I had lived 100 years past, sparked a curiosity that made me veer off from my desk to explore.

Growing up an hour away in the San Francisco Bay Area, Monterey was not a place I ever visited, just a town I drove through on my way to Carmel, which interested me far more for its artist-colony past. I had vague bits of historical knowledge–John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row, the aquarium opening to fanfare in the mid- ı980s–but not much else. So I did as I always do in a new place: I went looking for the old places. We leave a part of ourselves in the spaces we live, love and spend time in–a soul print, if you will, and these are the places I seek out. That’s what took me to 800 Cannery Row, a ramshackle building sandwiched between two old canneries, one now a hotel, the other a souvenir shop.

It’s a flat-roofed, weathered wood building with a row of windows looking down on the street. Originally, it was a single-story home for a family of sardine fishermen, complete with curing tanks in the backyard. In ı928, it was purchased by a marine biologist named Edward Flanders Robb Ricketts to house his company, Pacific Biological Laboratories, and eventually himself and his family.

Ed Ricketts was, by all accounts, a magnetic personality in real life. But it’s Steinbeck’s portrayals of him on the page that created the cult-like status that surrounds him and this humble building to this day. Steinbeck turned Ricketts into the Cannery Row character “Doc,” and collaborated with the scientist on the explorations recorded in The Log From the Sea of Cortez. If the connection to the famous author saved Ed Ricketts from being obscured by time, that’s no more than he deserved.

He was, by and large, a self-taught marine biologist. He worked outside of academia, making ends meet by selling biological specimens–frogs, cats, marine invertebrates, et cetera–to schools and labs. As he collected specimens for his business, he observed and studied the marine life of the shore, called the intertidal zone. These studies culminated in the ı939 book Between Pacific Tides. Today, the book is seen as a foundational text for marine biology and ecological thinking. When it was published, its focus on the web of relationships between different species was ahead of its time.

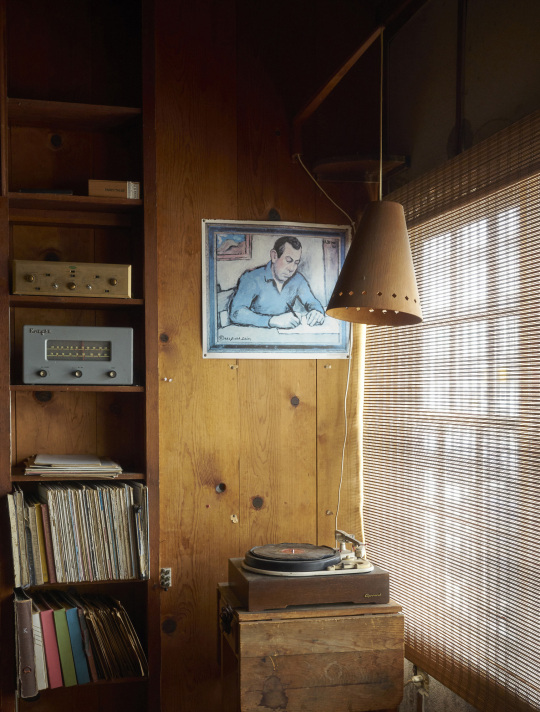

This sensibility, his way of observing relationships between living things and their environment, colored the way he navigated his own life as well. Ricketts is remembered as being kind to others regardless of station in life–nonjudgmental, a great listener, a bit of a ladies’ man. His home, on what was then called Ocean View Avenue, was a meeting place for friends–remarkable, when you consider what his neighborhood must have smelled like, surrounded by a couple dozen sardine canneries, and more remarkable still for the cast of characters around Ricketts: composer John Cage, writer Henry Miller, local artist Bruce Ariss, mythologist Joseph Campbell and, of course, Steinbeck and his wife Carol. All would hang out into the wee hours to drink, philosophize and listen to whatever music happened to be playing on Ricketts’ old phonograph. (His taste ran to Bach, Lead Belly and Gregorian chants.)

There is today no separating Ed Ricketts from Steinbeck. “Doc would listen to any kind of nonsense and turn it into wisdom,” Steinbeck wrote in Cannery Row. “His mind had no horizon–and his sympathy had no warp. He could talk to children, telling them very profound things so that they understood. He lived in a world of wonders, of excitement.”

This life of the mind and senses ended tragically, just three days before Ricketts’ 5ıst birthday. While running out to get steaks and salad for dinner, his old Buick was hit by the Del Monte Express train a few blocks away from his home at PBL. It took him three days to die of his injuries, but I have heard that the first thing he said when the paramedics reached him was that it was not the train conductor’s fault.

Ricketts’ death loosely coincided with the decline of the sardine industry–a decline he predicted–and the building stood vacant for a number of years as the once-bustling industrial neighborhood withered around it. It was rented in ı95ı by Harlan Watkins, an English teacher at Monterey High School who lived there and would teach Steinbeck’s Cannery Row to his students by having them come to the place that inspired it and read it aloud. In ı958, Watkins moved to Europe, but not before convincing a group of men friends from the community to collectively buy PBL to use as a meeting house. Thus began the Pacific Biological Laboratory’s next incarnation.

The PBL Club, as they called themselves, was not a formal men’s club per se, just a group of guys that used the house to meet up regularly and have drinks, listen to music, make dinner, talk about ideas and whatever else was on their minds. All told, there were about 20 members over the years, among them notable artists and writers including three famed cartoonists: Hank Ketcham (Dennis the Menace), Gus Arriola (Gordo) and Eldon Dedini (best known for his iconic comics in Playboy). Many members were avid jazz fans, and one evening in the “Party Room,” the idea was hatched for a jazz festival in Monterey. In October ı958, the first Monterey Jazz Festival kicked off with performances by Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Max Roach, and was one of Billie Holiday’s last shows. The PBL became the festival afterparty spot, scene of impromptu sets in the backyard by jazz luminaries. By that point there was no chance of disturbing the neighbors. The area was so deserted there were weeds growing in the street.

Over the years, Cannery Row has been rejuvenated as a tourist destination, anchored by the Monterey Bay Aquarium and the history of the old cannery days. Through it all, PBL continued on as a men’s club, and a witness to the passing of time, physical vessel of Ricketts’ legacy. In ı993, the last surviving members of the original PBL club sold the building to the city of Monterey with the understanding that it would be preserved and shared with the public for free. That promise has been kept.

It took over two years for me to actually walk through the door of PBL and stand in the rooms where all these stories unfolded. As I waited through the pandemic and the Brigadoonian hours for tours (only on the second Saturday of the month), I had built up expectations of what I would find. Ed Ricketts raised up the original single-story house and added a ground-floor laboratory and garage, so the entrance is at the top of a flight of old wooden stairs.

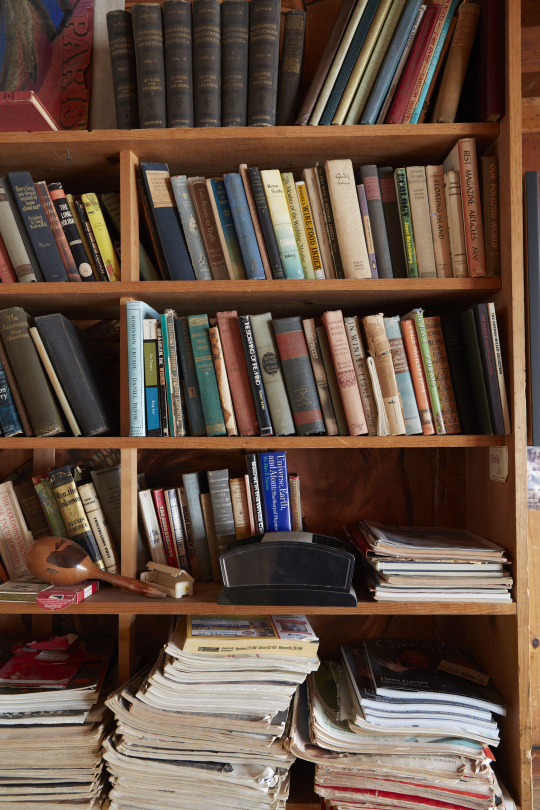

The walls of both main upstairs rooms are covered with a pastiche of pictures clipped out of magazines, museum prints of paintings by Botero, Goya, Matisse and others, music posters of jazz greats, and photographs of club members and of course Ricketts and Steinbeck. The front room was used for playing cards and chess and listening to music from the ample record collection. The stereo and record player are watched over by a painting of a writing John Steinbeck by local artist Judith Deim, hung right next to the front window so he has a view out to the street he immortalized.

Through a blue door covered with various coats of arms sits the Party Room. A piano on the right, a long bar along the opposite wall, the windows at the back of the house look out to the bay. Behind the bar, a series of wood cubbies are filled with various bottles of the club members’ favorites tipple, each cubby labeled with the corresponding member’s name, and a door leads to a tiny galley kitchen that is not much different from when Ricketts lived there, I imagine. The painting of a voluptuous female nude hanging above the piano I recognized as one of Dedini’s, no doubt from seeing his work in my grandfather’s old stash of Playboy magazines in his garage. Next to it but hidden behind the door from the front room is another of Dedini’s illustrations–this one of Louis Armstrong on a poster for the first Monterey Jazz Festival.

The door off the Party Room leads to a balcony and set of wood stairs that access the backyard of the property. This is where those impromptu musical performance would take place, next to the large cement tanks once filled with “little beasties,” Ricketts’ affectionate name for the specimens he collected. And beyond it all, the Monterey Bay laps quietly and calmly on the rocks. In Ricketts’ day, this stair access to the yard did not exist. The only way to enter was through the backdoor of the laboratory and garage on the ground floor.

Even though the original contents are now in the lobby of the Monterey Bay Aquarium just down the street, Ricketts’ old lab still has a few old bottles and specimens sitting on its raw-wood shelves, and a large travel desk that was made for his specimen-gathering expeditions but proved too unwieldy for travel.

It’s a ghost of the room it once was to be sure, but there is enough there to imagine how it used to be–a smelly workplace filled with slimy, fishy things being preserved in jars, and all the equipment needed to do so hanging from its walls. This was undeniably Ed Ricketts’ soul space: the place where he spent the most potent, and I hope happy, part of his life. It is where he was rooted in his life’s purpose. His genuine interest, appreciation and acceptance for all types of earthly creatures made this humble wood shack the unlikely epicenter for groundbreaking ideas in marine biology, literature, art, jazz history, and was a symbol for California bohemia itself.

I have spent a fair amount of time within these rooms now. I have photographed the space in depth and have been able to scan the art on the walls and the books still on the shelves from the PBL club days, and ogle the specimen jars and Ricketts’ carefully typed notes on color-coded index cards in his former lab. I have yet to tire of exploring it. And at noon, that steam whistle that originally lured me here is a deafening and jarring surprise. It turns out the whistle is right next door, a siren’s call not only to the past but to Pacific Biological Laboratories itself.