In every book I have made there has been a chapter that for some reason or another has not made it into the final book. Each time it is a heartbreak, but I generally know early in the layout process, before any writing takes place. That wasn’t the case with Still Lives. At the eleventh hour I had to make the difficult decision to take out one of the most meaningful chapters in the book, the chapter on JB Blunk. The only reason that I made this decision was because I had included Blunk in Handcrafted Modern. That and I was determined to include key points and my favorite images in the Introduction of Still Lives because it was so important to the making of the book as a whole. And still, this chapter, both images and text, is too beautiful not to share it here in its entirety.

If there is an artist whose home I know intimately, it is JB Blunk’s. Funnily enough, I never met the artist himself. But over the years, since I first photographed his home for my book Handcrafted Modern in 2009, I have returned countless times to photograph, to write, to visit, to stay, and to help with events and fundraisers whenever needed. My relationship started with a cold call to Blunk’s daughter, Mariah Nielson, to ask permission to include her family home in my first book. Not only did she enthusiastically allow me to do that, she invited me to stay in the house alone, to catch the ideal sunrise light to photograph the exterior.

To be in this house at any time is special, but experiencing it alone, padding around the dewy early morning yard in pajamas at sunrise, seemed like a gift I could never adequately repay. This generosity and the dedication to art being created on this property is embedded into the DNA of the Blunk family and cemented by JB himself. The family has taken JB’s wish that art continue to be created here as its guiding tenet in preserving and nurturing JB’s legacy. In 2007, in collaboration with the Lucid Art Foundation, they founded the JB Blunk Residency. The program hosted twenty-two artists and designers in the home and studio. But at its heart, this place is still a family home that also happens to be the masterwork of JB, the artist who created it over years of life and use.

James Blain Blunk was born and raised in the small, midwestern town of Ottawa, in eastern Kansas. He headed to California for university, first studying physics at the University of California, Los Angeles, before changing his major to art and studying under noted ceramicist Laura Andreson. While there he developed an affinity for Japanese pottery, first through British potter Bernard Leach’s book A Potter’s Hand and then at an exhibition of Japanese potters at Scripps College, in which Shoji Hamada’s work in particular stood out to him.

Something in the Japanese aesthetic struck a chord for Blunk and he decided he had to figure out a way to get himself to Japan. As fate would have it, shortly after he graduated in 1949, the Korean War broke out and he was drafted into the army. While serving in Korea, he found himself in Japan on a short training trip in 1951. On his day off, Blunk wandered into a mingei crafts shop in Tokyo that carried many of the potters he had admired from the exhibition in California. He went inside to inquire about Hamada and by chance met the artist Isamu Noguchi and his new wife, actress Yoshiko Yamaguchi, who were browsing in the shop and happened to overhear his inquiries about ceramics. It turned out that the couple was staying with ceramics impresario Kitaoji Rosanjin at the time, where Noguchi was experimenting with clay. By the end of this first meeting, the couple had invited Blunk to visit them at Rosanjin’s compound in Kita-Kamakura. He did indeed visit them and was introduced to Rosanjin, who invited Blunk back to learn from him. Thus began Blunk’s lifelong friendship with Isamu Noguchi and set him on a path to apprenticing and learning ancient Japanese ceramic techniques from some of the country’s living legends—the very masters themselves.

After being discharged from the army in Japan, Blunk headed back to Rosanjin’s compound to take him up on that invitation. He stayed for four months, working and learning and serving as Yamaguchi’s driver when Noguchi was away. It is believed that Blunk met his next sensei (teacher), Kaneshige Toyo, while at Rosanjin’s compound. Kaneshige specialized in the Bizen tradition of wood-burning-kiln firing of earthen red clay with unglazed surfaces. One day, Blunk decided he wanted to be in Bizen and learn from this master. So he packed his belongings and turned up, unannounced, on Kaneshige’s doorstep in the town of Inbe. After that awkward meeting, Kaneshige accepted Blunk as his apprentice. Blunk worked closely with the master for the next two years, learning all aspects of the Bizen tradition, from studying kiln construction to turning his sensei’s wooden pottery wheel, a task that was one manually.

Blunk returned to the United States in 1954. After a short stint teaching in Southern California, he made his way to San Francisco, where he showed the Bizen pieces he had created in Japan with limited success. Glazed mingei pottery was popular at the time, so the American eye was not accustomed to the Bizen technique, which used just “earth, water, and fire.” Around then, in 1955, Noguchi again made a life-changing introduction. He introduced Blunk to his friend the artist Gordon Onslow Ford. The two artists shared an interest in Japanese aesthetics and arts and quickly formed a friendship. Onslow Ford’s studio was located aboard a decommissioned ferryboat called the Vallejo, across the bay from San Francisco in the town of Sausalito. The boat was also the cultural meeting place for an esteemed group of artists and thinkers, and Blunk quickly integrated into Onslow Ford’s inner circle of friends.

When Onlsow Ford and his wife, Jacqueline, were planning to build a new home on some property they purchased in West Marin near the town of Inverness, he asked Blunk to be involved. In addition to helping find the right site on the land to build the house, Blunk aided with the building of that structure’s most complex feature, its curved roof. In 1958, the year Onslow Ford’s home was built, he and his wife invited Blunk and his first wife, Nancy Waite, to choose a spot on their land to build a home and studio of their own. The building of this home would shift Blunk from ceramicist to sculptor and integrate wood into his art practice as a favored material for the duration of his life.

When I first learned of JB Blunk, it was his handmade wood furniture that lured me in. Handcrafted Modernfocused on architects’ and designers’ homes, and Blunk and his one-of-a-kind chairs and stools gave me license to include him as a bit of a wild card. The house itself is really more of an Eastern-inspired modernist cabin, no doubt a nod to his time in Japan. Because the couple were on a tight budget during its making, all the materials that were used to build it were found timbers from beaches and forests or salvaged existing materials (such as windows and doors) that were fitted into the structure in newly repurposed ways. Beyond that, everything was created for the house over the years as funds would allow—from unique doorknobs and light pulls to furniture and fixtures. The size and shape of the original open-plan structure was determined by the length and width of the timbers that were found. And as with all homes that evolve through a lifetime of living in them, additions and embellishments were simply added when needed or when inspiration struck.

When I began making my books, I became acquainted with the notion of Gesamtkunstwerk in architecture, the idea that everything that goes into a structure—shell, furnishings, landscape, and accessories—are all designed or made by one artist or architect or designer. In my experience this turns out to be more of an aspirational goal than literal one. But here, in Blunk’s home, that label rings true. From the arch you walk under to reach the front door to the unique doorknob you use to enter the house itself; everything here is touched by Blunk’s creative prowess and playful nature.

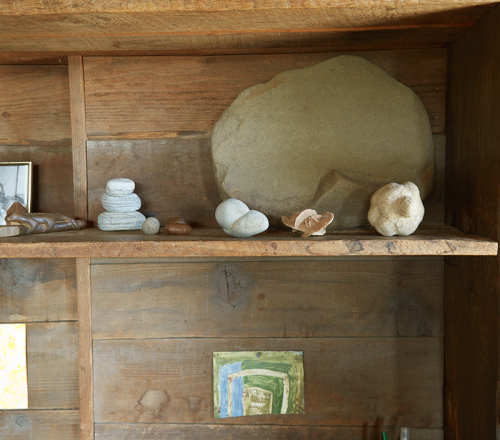

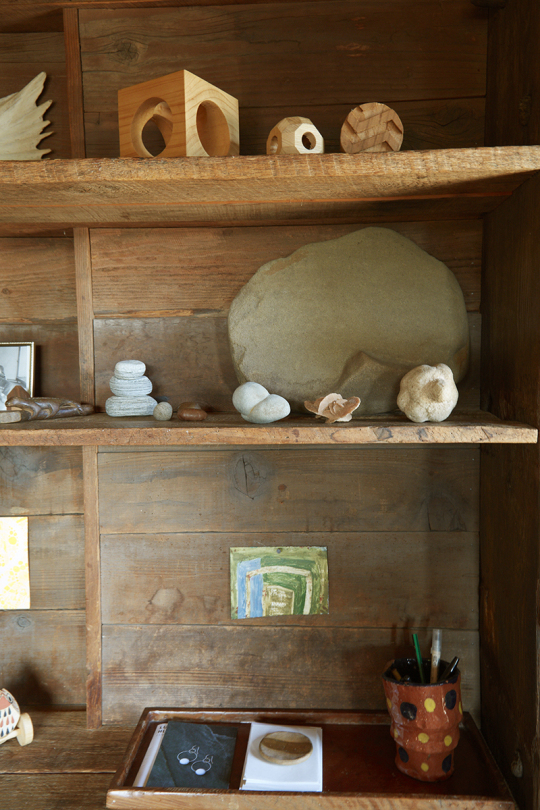

The main room of the house is a multipurpose space—a combined living room, dining room, and kitchen with an enclosed pantry. A small entry area, hidden behind a wood partition, greets you upon entering, with a place for hanging coats, the stereo system, and the Blunk family’s record collection all hidden behind bright red and blue curtains. Next to it is the small alcove where Blunk’s “Scrap Wall” is installed, made from the redwood scrap pieces from his monumental sculpture The Planet (1969), which is in the collection of the Oakland Museum of California. More Blunk sculptures live in this little space as well, but the same could be said of every space in the house; handmade stools and sculptures migrate around to make unique arrangements every time I visit. This is all part of the masterwork. Off the north side of the house, through a glass door, sits the bathroom, with a compost toilet, claw-foot tub, and sink carved out of a chunk of cypress wood, detailed with ridges made by a chisel. The main living space has seating around a log stove (the only source of heat) in the center of the room. A long table, used for dining and work, forms a natural separation for the kitchen area on the east side of the house. Out the kitchen door, on the deck that overlooks the valley, is a small utility room that holds the modern conveniences of a washer and dryer and a flush toilet for those not brave enough to compost.

Back inside, a ladder in the center of the living area leads up to a small loft that served as a bedroom for Mariah and her two older brothers, Bruno and Rufus, as evidenced by their stickers and penmanship that still can be found on the walls and desk. The bedroom that was added in 1985 sits behind the door at the top of the ladder. I can attest that there is no sleeping late in this room. With no curtains on the picture window and the bed positioned to see the sun rise, you are guaranteed to wake with the earliest birds. A wall of books, a wood desk, and more sculptures complete this room and another door leads out to the yard. All the furniture and artwork within the house, down to the smallest object, is by Blunk, his family, or friends.

For the first few years after my initial visit, when I would photograph the artists in residence, I made note of the subtle changes and shifts in artwork around the space. Now I find myself thinking of the pieces that have been sold to collectors and museums, like the Scrap Chair, which originally sat under the ladder to the bedroom. It is now in the collection of the Museum of Craft and Design in New York City. Other pieces have been sold too, as love for Blunk’s work continues to grow. Often the proceeds fund the demands that living in such a home entail.

The inspiration for the preservation part of this book is in part due to my witnessing the absolute care, thoughtfulness, and unrelenting work that is always taking place in this house. It is a fact that houses need upkeep, and rustic, rural homes, like this one, have extra special challenges that are ongoing and completely separate from the fact that the structure itself is a piece of art. Mice, carpenter ants, termites, water damage, and the never-ending danger of fire are just a few that come to mind. Yet Mariah stewards Blunk’s legacy and she and her mother, JB’s second wife, Christine Nielson, still live in the house part time. They do not treat the house as a precious artwork in any way. It is that, of course, but it is also home. Blunk himself considered the whole property—house, studio, garden, and more—one big sculpture. But it is a living sculpture, breathing, changing, and evolving as the life and lives within it do the same. The family moves forward with JB’s artistic spirit as their guide. Let the house and studio continue on as a place for making art or let the land reclaim it as its own: Those were the two options as JB saw it. For now, its artistic legacy continues.