Charles de Lisle

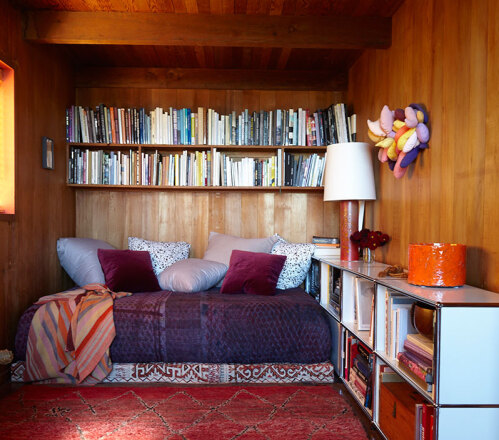

Charles De Lisle is best known as an interior designer, but after years of friendship I have come to know he is an artist at heart. We met years ago when I was a shopgirl at William Stout Architectural Books and Charles was an interior designer just trying to buy a pile of books. The backstory of our first meeting still makes me laugh, but without going into too much detail, let’s just say I was familiar with his work and I am pretty sure he walked away thinking I was a weirdo design groupie. Thankfully our paths kept crossing and we had more and more friends in common and I transcended being a kook to a friend. Since I have known Charles, he and his husband, fellow designer Ralph Dennis, have lived in the house that Bay Area architect Donn Emmons designed for his family in 1949 in Mill Valley. Built on two levels with a wall of windows that looks out to the San Francisco Bay, it is a modest-sized, 1300 sq. ft. home with a tiny kitchen but a perfect backdrop to these two designers’ lives. They rented the house from the Emmons family and became caretakers of sorts for this piece of architectural history for the past ten years. Living in a rental meant their design fingerprints were constrained like they rarely are on their work projects. I’ve always thought that was good for them somehow, allowing for more relaxation at home because they could not change the structure in the slightest. I had long planned to include these images in a future book on interior designers’ own homes but as Charles and Ralph move into a new home, it felt like the right time to finally share these images of this beautiful home they created for themselves.

Carina Seth Andersson

This piece ran in my People Watching column for the NYTimes T Style online.

Exquisite simplicity: If I had to describe Swedish glass artist Carina Seth Andersson‘s work in a quick sound bite, that would be it. When I first met her, I was already enamored with her series of hand-blown perfume flacons, each made especially for its own vintage glass stopper: a perfect marriage of old and new, and also an object I could actually use. Andersson’s work always feels refreshingly thoughtful; she makes objects to savor for a lifetime.

Originally a textile design major in college, Andersson quickly realized that two dimensions were “not enough” for her. Her desire to “work with forms” and a curiosity about glass led her to Orrefors Glass School in southern Sweden. “And then I was hooked!” she says with a laugh. Since earning her M.F.A. from the Stockholm design school Konstfack in the early 1990s, she has moved fluidly from project to project, designing for clients (like Iittala, the legendary Stockholm design shop Svenskt Tenn and most recently the Swedish fashion brand Hope), producing her own work in small runs, and hand-blowing pieces for galleries. Her work is rooted in a fascination with “really good everyday use things,” she explains. “But you take a little bit longer with them.”

This ethos extends to her personal world. During my visit to Andersson’s studio in Varmdo, we took an impromptu jaunt to her summer house in Skagga, about 20 minutes away. The seamlessness between the two spaces is striking. In each, objects are neatly arranged on shelves, and the essentials serve as decoration.. Andersson and her husband, the architect Fabian Pyk, designed the house 12 years ago but it feels timeless.

When I asked Andersson what she had on the horizon, she mentioned a public-works project for a hospital in Lindkoping; making small clay pots, especially for bonsai trees; and a side project curating shows that showcase Swedish crafts abroad. When I inquired about her perfume flacon project, imagining that she had exhausted her collection of vintage stoppers, she corrected me: “I have a lot of them, so it is not the end.” And it’s clear that she’s not in a rush. For Andersson, simplicity takes time.

If you’d like to see the original post with image captions, you can see that here.

Charles Bello

This piece originally ran on the NYTimes T website as part of my People Watching column.

Charles Bello may not be a household name, but he has a cult following in certain circles. He came to my attention via a circuitous route that started with an e-mail from Raymond Neutra (yes, like Richard Neutra, the Modernist architect; Raymond is his son). Raymond had received my book, “Handcrafted Modern” (Rizzoli), and with his compliments he mentioned that one of his father’s former interns — Bello — might be of interest to me. This was a man who dropped out in the 1960s, bought 400 acres of redwoods in Northern California and, with the help of his wife, built a number of houses and structures by hand there, Raymond said. He attached one picture, of two people sitting in front of a wall of windows with a ridgeline of trees in the distance. I was sold.

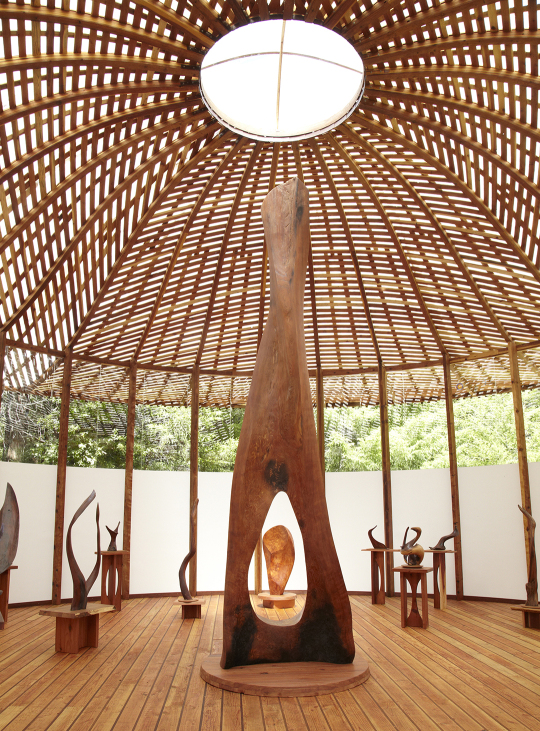

The drive to Bello’s is not for the faint of heart or ye-who-lacks-four-wheel-drive. As you pass the last locked gate and pulling onto the property, a round structure emerges out of the redwoods: the newly finished art gallery, a building whose roof is made of wood lattice and a translucent material that makes the light glow inside. It was here, snooping, that Bello found me.

A tall man with a cloud of white hair and suspendered pants, Bello is the sort of guy whose choices were not the obvious ones. An intern for Richard Neutra in the 1950s, Bello also worked for the architect Henry Hill and the landscape architect Robert Royston. A brief foray into photography once brought him to a meeting with Edward Steichen, and talks of being included in an exhibition. When Bello met the structural engineer Pier Luigi Nervi in Italy and asked him if he thought Nervi’s ferro concrete curvilinear forms could be done in wood, Nervi responded: “There is no wood in Italy. Go home and do it in California.” So he did. Bello’s path is one of material exploration, and though he had the résumé for a successful career in architecture, his choice in 1968 to buy this bit of wilderness in California with his wife and sons and live here forged a life now filled with deep purpose. He is a steward of the land.

When I think of people “living off the land” or “dropping out” in the 1960s, this is not the place I imagine. A tour of the property in Bello’s “Little Buddy,” a mini 4×4 open-air all-terrain vehicle, reveals a compound of houses and structures built over the course of 44 years. There’s the A-frame house (1968) where he and his late wife, Vanna Rae, raised their two sons, and the larger three-bedroom house (1982) near the creek, which was intended as an upgrade from the A-frame. But Bello “never did like that structure much. It is too heavy for my taste and I prefer the curvilinear, softer, lighter, forms better,” he said. A long, white-knuckled ride around the property’s dirt roads and trails (approximately five miles of each) includes crossing the five concrete arched bridges he built. Bello logged all of the lumber used from his own land — some milled by a saw rigged up to a 1965 Ford Galaxy.

When the air turned chilly, we headed back to settle in and make dinner (lentil soup, bear meat — surprise! — and fresh salad from the garden). My accommodations: the Parabolic Glass House (1989), the very one I had seen in that original e-mail from Raymond Neutra. Featuring a curvilinear wood roof (à la Nervi), the structure is made of two curved walls of windows that achieve Bello’s desired effect: to be enveloped in trees. The majority of the furniture in the house is of Bello’s design and make, including the dining chairs, each made from a single plank of redwood, and one more modern chair, a one-off. The couch is nestled along the stone dividing wall in the perfect spot, so that you may enjoy the fireplace and the expansive view all at once. Bello left me there for the night with a newly lit wood stove, a cup of tea and the sound of wild frogs breaking a silence that can only be experienced so far from civilization.

To learn more about Charles Bello and his organization, the Redwood Forest Institute, go to savetrees.org.

You can see how this piece originally ran in the NYTimes here.